No products in the cart.

Tour ends here.

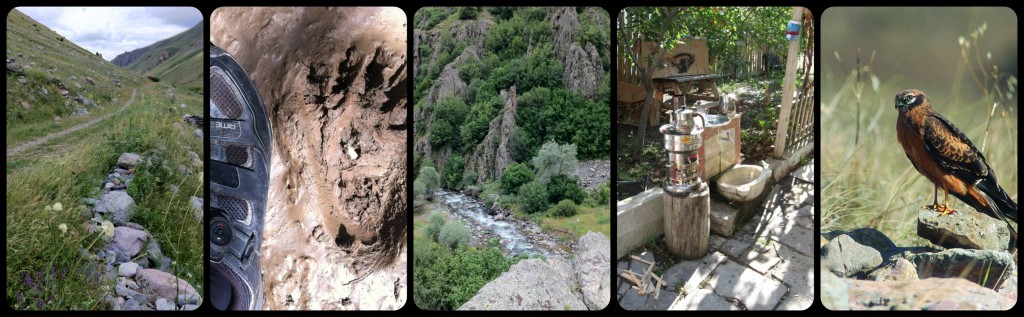

The Kackar Mountains are a different world from the rest of the country and Turkey’s most northerly range. High, superbly green alpine meadows nestle under towering granite peaks- snow covered for most of the year and often shrouded in clouds. The Kackar are home to some of Turkey’s most friendly people and some of its most fantastic wildlife, and you’ll be one of the first to ride these trails. This adventure biking tour incorporates challenging terrain and immense views, with plenty of natural, historical and cultural interest along the way too.

The 9-day long tour links the Kackar and Mescit Mountains via the awesomely beautiful Coruh river valley. Most routes are over unsurfaced forestry trails or inter-village dirt roads but where possible we ride on rough tracks and singletrack mule trails too. We stay in comfortable pensions and friendly village houses and have the chance to meet people alive with rich traditions. Note that the Kackar are a “big mountain” range and as such weather conditions can be unpredictable even in mid summer. So it’s essential to come prepared with appropriate, warm, wind proof and waterproof clothing.

Please note- this tour is also possible on regular “bio bikes”, but you do need to be in good shape and used to a lot of climbing!

Click here to view the full itinerary.

The Kackar are our favourite alpine range and offer a sense of remoteness and exploration that belies their geographical area. There is plenty of fine singletrack to explore and the riding can be as tough or as easy as the group chooses. The whole area is a protected environmental zone and there are real opportunities to see raptors, gamebirds, wild goats and bears. Add in legendary local hospitality and endless breathtaking mountain panoramas and you have an unbeatable, wilderness trail experience.

The Kackar peaks and passes where we ride are covered in snow for up to 10 months of the year. Late June, July and August are the best, sometimes only months to visit without special equipment. Early season is when you’ll see Turkey’s finest snow melt wildflowers, plenty of snow on the peaks and a better chance of seeing bears and other wildlife.

Erzurum is the nearest national airport and the tour starts and finishes there. Turkish Airlines offer scheduled services via Istanbul.

Day 1: Transfer from Erzurum Airport to Uzundere

We meet you at Erzurum Airport and then drive approximately an hour north to our base in the small town of Uzundere. After some settling in time (and lunch if your flights arrive early), we visit the Tortum lake and waterfall- beautiful natural features that were created after a huge landslide in the river valley. We stay in a pleasant, family run pension with private bathrooms and a quiet, shady garden where we can prepare the bikes for the tour. You can leave excess baggage and bike boxes here, as we will return here towards the end of the trip. Dinner in hotel and tour briefing.

Day 2: Transfer – Haho Monastery – Uzunkavak – Devedaği – Arakoy – Ispir. 50km / 1000m Climb / 2500m Descent

This first day’s ride is relatively easy in terms of terrain, distance and climbing- so you can gently acclimatise to the elevation and enjoy the amazing landscapes. We begin the day with a 45km (1.5 hour) transfer from Uzundere and en route visit the 12th Century Georgian monastery at Bagbasi. We continue by minibus, steadily climbing towards the Devedaği Pass and the main ridge of the Mescit Mountains. We begin cycling from the 2570m pass, enjoying incredible views over the entire Kackar massif and wonderful wild flowers in early season. Descending on a well surfaced dirt road we pass through mature pine forest, and stop at the small village of Devedaği for a morning break. We carry on along an undulating dirt road that climbs to incredible vantage points over the Çoruh valley- and we stop for a picnic lunch in one of the more beautiful spots. The road improves as we descend into the main river valley and pass by the small town of Ispir, where we can admire the Byzantine castle. We overnight in luxury air-conditioned wooden bungalows on the edge of the Çoruh river, and enjoy a good meal in the hotel restaurant.

Day 3: Transfer – Moryayla – Yedigoller – Yedigol – Aksu – Çamlikaya. 51km / 1000m Climb / 2340m Descent

Today we begin with a transfer out of the Çoruh Valley, to an area of beautiful open scenery reminiscent of the Scottish Highlands. We stop for a break in the small village of Moryayla- deserted apart from during the summer months and with no shop or cafe, the feeling of remoteness is quite wonderful, and amongst the unchanging pastoralism of mid-summer it feels like we’ve entered another time. From Moryayla, we continue climbing in the support vehicle, starting our ride approximately 2/3 the way up the hill. A steady yet challenging climb gets us to one of the high points of the tour- both in terms of elevation and views! The dirt road climb is increasingly steep, crossing wild, open moorland and then following a stream to reach the head of a steep valley. After some steep switchbacks to the 3200m pass we take a good break, on a vantage point high above the Seven Lakes (Yedigoller). Descending through the lakes on classic singletracks we spend some time here before going down into the main river valley. This section is unrideable, and we have to walk down a steep, rocky slope with our bikes for around 30 minutes- make sure your shoes are suitable! The rocky tractor track we pick up is difficult at first, but becomes easier as it drops down into a wonderful wooded valley. Continuing past the villages of Yedigol and Aksu we cruise effortlessly back down into the main Çoruh valley, completing the ride on an asphalt climb at the entrance of a new dam lake. We stay in a delightful old village house, and enjoy fantastic traditional local food in the lush garden surroundings. Note that we will stay communally in two rooms on basic mattresses.

Day 4: Transfer – Çamlikaya – Basmesra – Sirtbaş Yayla – Sirakonaklar. 25km / 1180m Climb / 1330m Descent

We begin the day with a guided walking tour amongst the gorgeous gardens of Çamlikaya, meeting local people and exploring wonderful green alleyways between the houses. With no road access to most properties, the villagers here still live a blissfully cut-off lifestyle reminicent of another time. The route starts with a short transfer up an increasingly rough mountain track to Basmesra village, where we begin a tough but steady ascent to a 2500m mountain pass, taking our time on the rough road, and stopping frequently to enjoy the gorgeous stream valley along the way. The route runs through thick forest, past traditional villages and up to an alpine pasture covered with flowers in the early season. We will also have the chance to meet the shepherds that live on the mountain tops throughout the summer. Our descent is via a singletrack trail that is the original mule access to the high pastures. The trail is technical in places, and those with less off road experience will prefer to walk certain sections, but the beautiful forest landscape and remote villages on the way more than compensate. Another singletrack takes us down through terraced hay fields to an Armenian church (now a mosque), before we begin another steady climb towards the main Kackar massif and the glorious traditional mansions of Sirakonaklar. A singletrack circuit of the village completes a tough, yet short day, and our comfortable hotel is most welcome.

Day 5: Sırakonaklar – Köprügören (Hoşnak) – Tekkale – Yusufeli – Transfer. 80km / 800m Climb / 1200m Descent

This longer ride takes us north east along the Çoruh valley, juxtaposing the valley’s natural wonder against the inevitable changes caused by the building of an extensive hydro-electric project. It’s a long and remote journey with plenty of interest and an ever-changing landscape. Beginning with a short but entertaining section of village singletrack, we descend on a well-surfaced road but turn off on an incredible dirt access road that contours the valley as it drops away below us. High up on the mountain slopes here we may well see ibex, and the views of the reservoir below are breathtaking! We stop for a good lunch in Koprugoren and pass by untouched valley scenery on our way to Yusufeli- at the region’s centre. We meet our driver, and transfer up the Barhal valley, towards the Kaçkar National Park. Our base for the next two nights will be at the comfortable Barhal Pension, beside a clear, fast-flowing stream that swells with snow-melt in the early season.

Day 6: Barhal – Saribulut – Norsel Yayla – Barhal. 36km / 1250m Climb / 1250m Descent

Today’s circular ride through the lower reaches of the high Kackar takes to some very pleasant forest tracks, enjoying amazing views to the higher mountains beyond. It passes by old mills, forgotten mountain houses and lush, green “yayla” pastures. Starting off with a visit to the 10th century Georgian church, our morning climb should come easier than some of the others- the grade isn’t too severe and the trees shade us from the full sun. We picnic by a waterfall in a paradise scenery below the Satibe ridge- where, if we are lucky, we may see bears. There is an option to climb higher to Pişenkaya Yayla for those with any legs left! A fast 14km downhill stretch takes us all the way back down the Kısla Stream to the main valley, and back to our comfortable rooms and another night in Barhal.

Day 7: Transfer – Olgunlar – Hastaf Yayla – Dilberduzu Campsite – Deniz Golu. Approx. 15km / 800m Climb / 800m Descent

After an early breakfast we drive 30km further up into the Kackar National Park, making our base at the lovely pension at Olgunlar. The dirt road ends here, and we choose to ride or walk the 7km (mostly smooth and grassy) singletrack trail that climbs to the Mt Kackar basecamp at Dilberduzu (2820m). From here, an optional hiking ascent to the 2700m alpine lake of Deniz Golu is hugely rewarding- we simply leave the bikes when the trail becomes too steep to ride! The descent is pure singletrack heaven, as we speedily roll down the valley there are easy sections for novice riders and technical rock gardens for the more advanced! Short in distance, but perfect in every way!

Day 8: Olgunlar – Barhal – Yusufeli – Transfer – Kılıçkaya – Kılıçkaya Pass – Çamlıyamaç Village (Oskvank Monastry) – Uzundere. 80km / 850m Climb / 1500m Descent

Today’s ride is cut into two sections- the first being a long and hugely enjoyable downhill spin back down the Barhal valley, all the way to Yusufeli (54km on a mix of dirt, concrete and asphalt road). We take a rest as we drive 1.5 hours out of the Coruh valley again, heading once more back to our start point in Uzundere. We pass the charming small town of Kilickaya, and after a wonderful barbeque lunch in a forest chalet near the top, embark on long, steady descent, with unravelling panoramas of the Tortum Lake below, and once again the chance to see wildlife. From the 2300m pass, we have one of the longest and fastest downhills yet, dropping 1230m in height over the course of 20km. As we descend, the landscape gets drier and more barren, and we eventually reach the village of Camliyamac where we visit the 10th century gothic Georgian Oshvank Monastery. From here, an easy spin along a good road brings us back to our starting point in Uzundere. We then transfer on to Erzurum, after packing down our bikes, and enjoy one last night together there.

Overnight Rafo Hotel, Erzurum

Day 9: Transfer to Erzurum Airport for onward flights

Tour ends here.

Price (per person):

1900 Euro.

Minumum group size 6.

Maximum group size 12.

For groups smaller than 6 people a surcharge will be added to the price

Price includes: 8 nights hotel accommodation- sometimes basic. Transfers to and from Erzurum airport. Professional MTB guide. Full use of support vehicle. All meals, snacks and tea and coffee at mealtimes.

Price does not include: Flights. Alcoholic and soft drinks available at camps or restaurants and entrance fees to historical sites and museums. Tips for guides and driver.

Tour Length:

9 days.

Start / finish point:

Erzurum.

Grade:

3-4: Challenging and relatively strenuous but with a hop-on hop-off support vehicle available.

Features:

7 days multi centre MTB. Some off road biking experience and good level of fitness required. Group size 6-12.

Recommended Dates:

July – early September: please ask!

Options:

Single Room: 400 Euro.

Bike Rental (Trek Roscoe 8): 360 Euros

eBike Rental (Trek Powerfly): 540 Euros.

Biking in Turkey is the cycling division of Middle Earth Travel: a fully registered travel agency with Turkish Tursab licence accreditation No. 3242. With more than a decade of adventure travel experience, enthusiasm and extensive local knowledge we are the best people to advise you on your Turkish cycling holiday experience!/p>

İsali-Gaferli-Avcılar Mahallesi Kuran Kursu Caddesi, No: 7 50180 Goreme Nevsehir TURKEY